I had the opportunity to speak with Victor Shapovalov, the founder and CEO of Zmiyar, one of Ukraine’s fastest-growing defence-tech companies. In a little more than two years, Zmiyar has produced over 20,000 devices for the Ukrainian Armed Forces, ranging from initiation boards for FPV drones to control modules for ground robots and Hydra, a system that transforms old Soviet mines into remotely monitored and remotely controlled devices. What distinguishes the company is less the range of products than the pace at which they are conceived, tested and delivered: design cycles counted in days, direct testing with frontline units, and a manufacturing chain kept largely in-house to minimise delays. Our conversation shed light on Shapovalov’s trajectory, his Kharkiv engineering background, the way he founded Zmiyar in response to an urgent battlefield requirement, and his hands-on leadership under pressure. It also offered a broader view of what it means to engineer in wartime Ukraine, the culture that has formed around this necessity, and the urgent technological needs the country’s defence sector must address.

Kharkiv’s Engineering Culture and a Career That Prepared Him For War

Shapovalov’s trajectory begins in Kharkiv, where he studied at the Kharkiv Polytechnic Institute, part of an engineering tradition defined by practicality rather than abstraction. He recalls that students were trained not simply to write code or draw schematics, but to evaluate immediately how a device would behave in real conditions. This “build and test” mentality, the instinct to validate ideas through field pressure rather than theoretical argument, became foundational once he began working on technology intended for combat. War leaves no time for multi-month development cycles. Prototypes must be tested directly in operational environments and improved without delay.

His professional path reinforced that approach. Software development taught him systems thinking and the ability to understand how different layers of a product interact. Hardware engineering exposed him to the constraints of physical components: tolerance to heat, space limitations, interference, durability. Later, as a product manager at Ajax Systems, Ukraine’s largest security-systems company and a major hardware producer, he learned to balance technical capability with user needs and to make decisions rapidly. When the full-scale invasion began, these experiences combined into a coherent framework. He realised he had the full set of competencies needed to build the technology soldiers lacked and to do so at the speed the war demanded.

A Company Built Around Simplicity, Reliability and Immediate Feedback

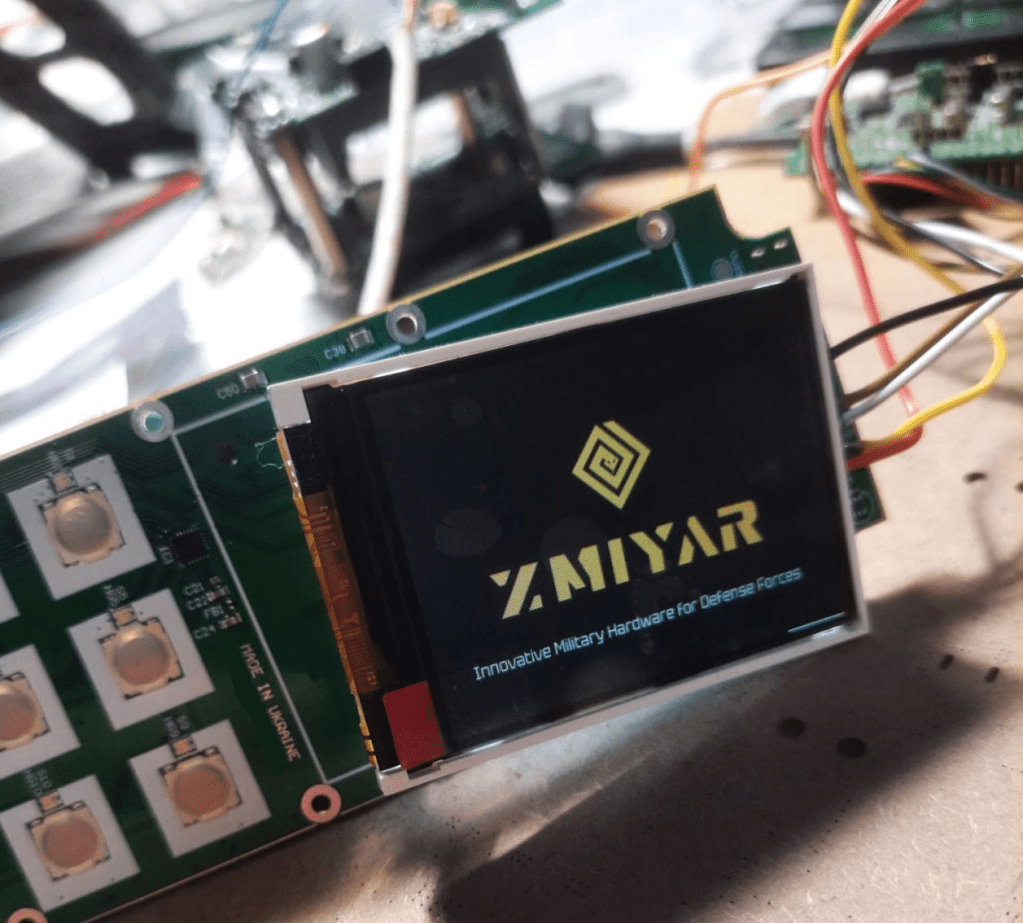

Zmiyar was created in November 2023 with a narrow and urgent idea: producing reliable initiation boards for FPV drones that could operate in any conditions. Initiation boards are compact electronic modules installed inside FPV drones. They handle the arming process and trigger the detonation sequence, making them one of the most critical components of the system.

From that starting point, the company expanded into a broader set of military electronics and control systems. Yet the principles remained the same. Devices must be simple, above all. Soldiers working under fatigue, stress or at night do not need complex interfaces; they need something that works without hesitation. “One connector, one button, nothing extra,” Shapovalov says, a philosophy reflected across the company’s products. High-quality components and careful circuit design are prerequisites, but the real test occurs in combat. Resistance to electronic warfare is integrated from the outset, and if anything proves unclear during frontline trials, the design is simplified again.

This approach extends to Hydra, Zmiyar’s newest innovation, a system that converts old Soviet mines into remotely controlled and monitored devices. Hydra upgrades each mine with sensors, communication modules and a remote-control board, transforming a passive explosive into a device that can be observed, activated or deactivated at a distance and integrated into a coordinated mesh network. Its immediate role is operational: safer deployment, more predictable behaviour, and unified control over entire minefields. But it also addresses the long-term problem of demining. Because each device is geolocated and can be remotely deactivated, post-war clearance becomes faster and significantly safer.

Scaling in Wartime: Speed, Autonomy and a New Engineering Culture

Over the past two years, Zmiyar has scaled at a notable pace, producing more than 20,000 devices despite the pressures of wartime conditions. According to Shapovalov, several factors made that possible. The company maintains direct communication with frontline units, which removes guesswork and accelerates iteration. Development and production cycles are intentionally short, driven by the assumption that delays cost lives. Critical manufacturing steps — CNC machining, board assembly — are kept in-house, reducing dependency on vulnerable supply chains. The team operates with a shared sense of urgency, and unusually for a wartime startup, Zmiyar has been profitable from the first months, providing financial stability in an uncertain environment.

Shapovalov situates this approach within what he calls a broader wartime engineering culture emerging in Ukraine. It is a shift defined by speed, pragmatism and improvisation within limits. Prototypes are built in days, tested immediately at the front and improved on the spot. When components cannot be sourced, a frequent occurrence, Ukrainian teams manufacture tooling themselves or adapt to alternatives. Bureaucracy is minimal, not by ideology but by necessity. “There is a specific problem at the front, we solve it,” he says. Compared to traditional defence companies with multi-year development cycles, this model is radically different. It is reactive, user-driven and tightly coupled to operational reality.

Responsibility, Pressure and Leading Through Uncertainty

Developing life-critical equipment carries a particular weight. Every device that leaves Zmiyar’s facility may enable a soldier to survive, or fail at a decisive moment. Shapovalov does not minimise that pressure. He personally reviews key design decisions and enforces multi-level testing, but the psychological burden remains constant. To support his team, he emphasises the thousands of units functioning reliably at the front, concrete reminders that their work has real impact.

Leadership itself is shaped by the conditions of war. Air raid alerts, blackouts, relocations, psychological strain and supply chain disruptions form part of daily operations. To cope, Zmiyar relies on clear processes, transparent communication and a focus on results rather than formalities. Redundancy is built into everything: backup generators, alternative logistics, parallel sourcing. Shapovalov sees calm as an essential part of his role, the team looks to the leader to absorb uncertainty so that the work can continue.

What Ukraine Still Lacks — and What Comes After

Based on direct conversations with units and his own experience, Shapovalov identifies several technological gaps Ukraine must address: stronger protection against electronic warfare; autonomous AI systems for reconnaissance and targeting; affordable, mass-produced EW tools; improved communication systems such as LoRa and mesh networks; and faster domestic production of ammunition and components. Another challenge is decreasing dependence on Chinese components, a bottleneck that affects many Ukrainian companies.

At the same time, he notes that the speed of Ukrainian defence-tech is often misunderstood. It is not a miracle or a cultural myth but a system built on urgency, decentralised decision-making and the authority for individuals to act without delay. Although the war drives innovation today, Shapovalov believes the underlying capabilities will endure. Technologies, expertise and companies created under extreme pressure will form a foundation for a competitive post-war industry.

For now, Zmiyar continues with the principle that has guided it from the beginning: build only what soldiers truly need and build it well.

—

Echoes from Ukraine / Valentin Jedraszyk

Leave a comment