It’s 10 a.m. when our screens light up with Maria Oleksa’s smile. Two days earlier, she and her team at Change.org France, in alliance with several associations and partners, had brought together nearly nine hundred people in Paris for Sky Shield, a civic call for a collective European air defence for Ukraine. This morning, the energy of that night still echoes. We can feel it together with my friend Lyubov Smachylo, a war-crimes investigator, whose guidance and reassuring presence accompany this first interview we conduct together. We listen as Maria speaks with the same measured precision and quiet authority that once guided her years in the newsroom, her calm expression a striking contrast to the urgency of the world she describes.

The Making of a Journalist

Maria was born and raised in Kyiv in a family that valued languages and education. From an early age, she felt an instinctive pull toward French culture and language, without knowing where it came from. Years later, when she moved to France to study media and communication at Sciences Po, she realized that Ukraine had never left her. Both worlds remained ingrained in her life. Two reflections of one another. Two cultures so deeply ingrained that each reveals the other.

“At first I didn’t think I would become a journalist,” she admits. “It happened naturally, almost by accident.” Her earliest experiences were in Ukrainian entertainment television, first with the local version of Star Academy and later as a production assistant for the channel CITI. Her real entry into journalism came in 2013, when she joined Euronews in Lyon and became part of the newly created Ukrainian service, one of the first of its kind. For her, the role was not only professional but deeply symbolic, a way of anchoring Ukraine in Europe’s shared information space. “Thirteen languages aired side by side,” she recalls. “And at last, Ukrainian was one of them.”

Euromaidan, a Baptism by Fire

In 2014, as the Maidan protests erupted, their work quietly took on new meaning. From France, Maria watched the Revolution of Dignity unfolds in Kyiv through the lens of Western television and felt a deep dissonance between what she saw and what she heard. “The words didn’t fit,” she explains. “If we don’t tell our own story, someone else will.”

That year became her baptism by fire. She realised how fragile representation could be, how a single choice of word or translation could shift the meaning of an entire struggle. In the studio, every report carried new weight. “We felt a huge responsibility,” she recalls. “Without Ukrainian voices in European media, the Russian narrative would have dominated completely.”

After Euronews came TV5 MONDE, then BFM TV, and finally Franceinfo TV, where over the years Maria became Deputy Editor-in-Chief. It was a position of coordination more than authorship, the role of deciding what goes on air and managing the tempo of breaking stories.

Reporting Through the Invasion

When the russian federation launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the team fell into a state of permanent alert. A dedicated section was created inside Franceinfo TV to cover Ukraine around the clock. “We had a team working almost nonstop,” Maria explains. “There was no real day or night, just the next update, the next alert.” The screens that once carried headlines now streamed live images from Kherson, Odesa, Lviv, cities Maria knew by heart. “Dozens of feeds arrived every hour,” she recalls. “Each one was a piece of someone’s life.”

The pace left no space for pause, only reaction, and the fatigue became constant. “You have to keep your voice steady while everything you love is under attack. You cannot allow emotion to take over, because the moment you do, the news stops. But inside, you break a little every day.” Then, almost as an afterthought, she adds, “The only advantage was that I wasn’t on camera, so no one saw my tears.”

She recalls one night during the blackouts of winter 2023, when Franceinfo TV and One Plus One co-produced a live broadcast linking two broadcast units. The operators and film crew came from a Ukrainian channel, turning the project into a moment of genuine cooperation. “It was three hours of conversation with Ukrainian guests, writers, artists, politicians, even someone from the national electricity company.” For Maria, it was one of those rare nights when television became more than coverage proof that even in darkness, connection endured.

Turning the Camera Toward Citizens

After months of covering the war, Maria began to feel the limits of what television could contain. The constant urgency of breaking news left little room for reflection. “Speed had turned into blindness,” she observes. “We were informing people, but we were no longer understanding what was happening.”

In 2024, she decided to step away from the newsroom. Her next chapter took her to Change.org France, where she became Country Lead. From the outside, it looked like a radical shift. But for her, it was a continuation of the same work. “Change.org is still an editorial space,” she concedes. “Only this time, the stories come from citizens.”

When a petition was launched calling for a European air defence for Ukraine (sign it here), she immediately joined the effort. It evolved into Sky Shield, a major public event that brought together nearly nine hundred people in November 2025 at the Salle Gaveau in Paris, where she was one of the speakers.

The Words That Remain After the Noise

Leaving television meant rediscovering silence and herself. Maria returned to the slower rhythm of writing, to the precision and solitude that television had taken away. For her, it wasn’t a departure from journalism but its quieter continuation, one that allowed her to linger instead of rush. “When you write,” she says, “you finally have time to stay with a thought long enough to understand it.”

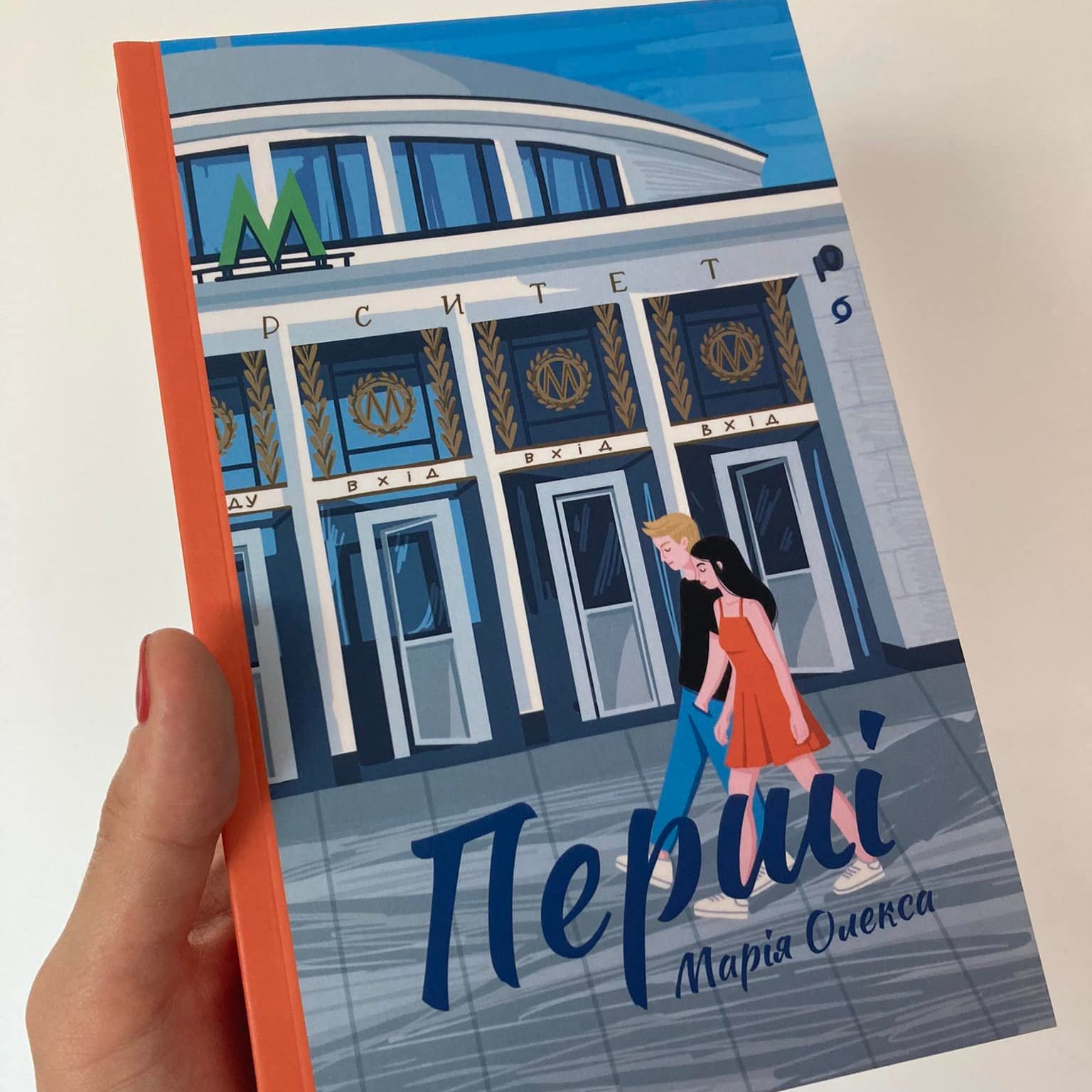

Her first novel, Перші (The First Ones), revisits Kyiv in the early 2000s through the eyes of two adolescents discovering a city and a country in transition. Her second, Кімнати Естер (The Rooms of Ester), follows a young girl confronting her father’s addiction, a story of pain and reconstruction that earned a place on the BBC Book of the Year Ukraine 2025 longlist. Five chapters of its French translation have already been completed with a professional translator, and Maria is now seeking a French publisher interested in the manuscript to support the translation and publication process. She is now immersed in the writing of her third book, delving further into the themes and emotions that have shaped her work to this day.

The Other Front of Culture

Through her writing, Maria has become a quiet defender of Ukrainian literature abroad. She often speaks of the imbalance that still shapes cultural exchange, how dozens translate Russian authors into French, while only a few carry Ukrainian voices across that same border. “It’s slowly changing,” she says, “but we’re still catching up with decades of silence.”

She often mentions Iryna Dmytryshyn, who for years almost single-handedly built the bridge between Ukrainian and French literature. Around her, a new generation of French translators has emerged, native speakers who learned Ukrainian and chose to dedicate their craft to it, a sign of the growing and renewed interest in Ukraine’s culture.

When we ask her, together with Lyubov, which Ukrainian book she would offer to French readers for Christmas, Maria doesn’t hesitate: The City by Valerian Pidmohylnyi. “I’ll definitely give a copy to my English-speaking friends,” she concludes with a smile. She also mentions Chapter Ukraine, a platform mapping every Ukrainian book translated abroad. “It’s a wonderful initiative and a proof that culture keeps moving even when borders close.”

The call ends slowly, as if neither of us wants to break the conversation. On the screen, Lyubov and I exchange a glance, both knowing that something has quietly shifted. What stays with us is not a quote or a headline but a feeling, the calm intensity of a woman who has learned to turn noise into meaning. When the connection fades, we sit there for a moment, hearts suspended between gravity and lightness, grateful that in the middle of the war there are people like her to remind us what endurance sounds like.

Leave a comment